If you ask eighth-graders if they are going to college, 95% of them say yes. But gaps between high- and low-income students develop throughout high school. By age 24, 82% of high-income students earn a bachelor’s degree. The completion rate for low-income young people plummets to 8%. Here’s a look at the numbers at key points in time:

| High Income Students | Low Income Students | |

| Say going to college – 8th grade | 95% | 95% |

| Say going to college – 10th grade | 80% | 60% |

| Graduate from high school | 94% | 70% |

| Begin college after high school | 84% | 41% |

| Finish college by age 24 | 80% | 8% |

Last year our team worked with a partner to create a picture of how these numbers map with dynamics that support or inhibit students reaching the college aspirations they all hold in middle school. You can explore a prezi of it here.

We support grantees and partners working to change these numbers in many ways. One project we’re part of aims to create new ways to help young people better navigate the college-going process. We partnered with College Summit and Facebook to launch the College Knowledge Challenge (CKC). My teammate Emily Dalton Smith designed and leads this project (and many others).

CKC is a $2.5m competitive grant fund for developers of Facebook applications aimed at making the college-going process more transparent, collaborative, and easy to navigate for low-income and first generation students. The goal is to spur the development of creative apps that make the most of students’ participation in the world’s largest social network. The CKC was open to for-profit and non-profit developers with ideas for great apps to help students in one of three ways:

- Helping students build, test, and implement personal academic pathways that grow out of college-career aspirations and are supported by informed decision making.

- Helping students build social capital and a college-going peer group.

- Rectifying information asymmetries in college admissions, financial aid, and college selection processes that disadvantage low-income and first generation students.

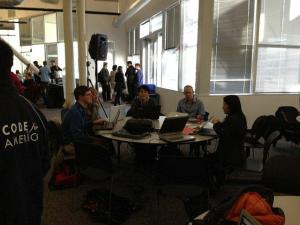

Last September, CKC kicked off with a day-long hackathon at Facebook headquarters with more than 100 developers, engineers, high school & college students and College Summit mentors:

The hackathon generated a ton of attention for CKC, and College Summit followed up with webinars and other resources to help developers understand key barriers to college for low-income young people. Experts were available throughout the fall to talk with app development teams if they had questions.

In the end, more than 100 teams submitted ideas to CKC. Last week a judging panel of students, experts in the college-going process, technologists, investors, and philanthropists selected 21 winners based on demonstrations of prototypes. Each winning team received $100k to further develop the apps. Next fall, all will be fully functional and widely available.

The project is an example of how our team is trying to catalyze more innovators to work on the same challenges in different ways, rather than always looking for the needle in the haystack. If you get a chance to poke around on the CKC website for more info about the contest parameters and the winners, let me know what you think!